Most B2B founders and marketing leads never planned to care about canonical tags. Yet once a site grows past a few dozen pages, canonicalization in SEO quietly starts to influence organic traffic, lead volume, and how clean reporting looks. When canonicalization is messy, search engines can spend crawl time on the wrong URL variants and split ranking signals across duplicates. When it’s consistent, the pages that matter most can accumulate those signals in one place.

When to use canonicalization in SEO

I think of canonicalization as a routing rule for duplicate or near-duplicate URLs. I’m telling search engines: “Treat this URL as the primary version, and attribute the signals from the other versions to it.”

In practice, I reach for canonicalization when the content is the same (or close enough that I want it treated as the same page), but multiple URLs still need to exist for real-world reasons. Common situations include parameterized URLs from tracking (?utm_…), referrals, and sessions; print-friendly versions; and category/listing pages that can be sorted or filtered into many near-identical variants.

When I don’t want the duplicate to exist for users anymore - because the page was replaced, retired, or the URL structure changed - I don’t use canonicals as a cleanup hack. In that case, I use a 301 redirects to move both users and crawlers to the replacement. And when a URL must remain accessible for a specific purpose but should not appear in search results, I treat that as an indexing decision (often via noindex) rather than a canonicalization decision.

One more nuance I keep in mind: canonicals can also be used across domains in syndication scenarios, as long as the content is genuinely very similar and there is clear agreement on which version should be treated as the primary source.

What is a canonical URL

A canonical URL is the single preferred version of a page that I want search engines to treat as the main source for indexing and ranking.

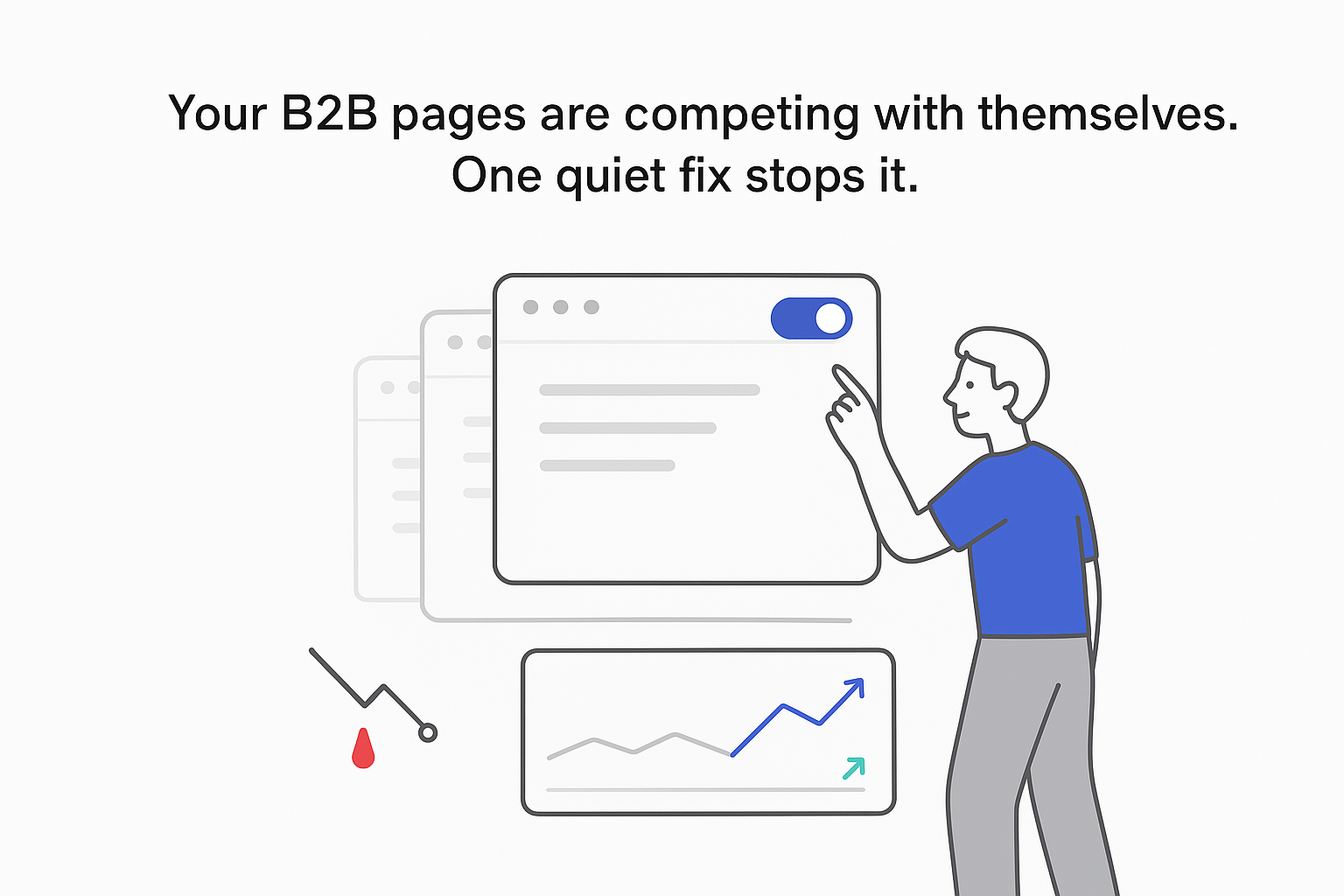

I declare that preference with a canonical tag (also called rel=canonical) placed in the <head> of the HTML:

<head>

<title>B2B SEO Services</title>

<link rel="canonical" href="https://example.com/b2b-seo-services/" />

</head>

The href value is the canonical URL. Pages that point to that URL are effectively saying, “This page is a variant; attribute the main value to the canonical.”

On pages that are already the preferred version, I still use a self-referencing canonical - a canonical tag that points back to the page itself. That creates a consistent source-of-truth signal and reduces ambiguity when parameters, trailing slashes, or alternate routes exist.

I also stay clear on what a canonical is not. It’s not a redirect (users can still land on non-canonical variants), and it’s not an absolute command - search engines generally treat it as a strong hint that can be overridden when other signals conflict. And it’s not a substitute for content decisions: thin or off-topic pages usually need improvement, merging, or removal, not just a canonical pointing elsewhere.

Purpose of canonical tags

Canonical tags are technical, but the payoff is practical. When I implement them well, they primarily help me consolidate signals so that search engines don’t have to guess which version should rank. Google’s own documentation on consolidating duplicates is a solid reference point: Google.

That tends to show up in a few ways: link equity is less likely to be split across URL variants, duplicate-version confusion drops, and crawl resources are less wasted on low-value parameter combinations or template-generated near-duplicates. Over time, that usually stabilizes rankings because one URL builds history instead of several similar URLs competing with each other - which matters even more when you’re dealing with limited crawl budget. For a practical B2B lens on crawl prioritization, see Crawl Budget for Small Sites: What Actually Matters and What Doesn’t.

Canonical tags also influence SEO performance indirectly but clearly: when the “right” URL consistently receives the consolidated signals, it’s easier for that page to rank (and stay ranked) compared to a situation where multiple variants cannibalize each other. If cannibalization is already showing up in your reporting, How to Avoid Cannibalization on B2B Service Sites pairs well with canonical cleanup.

I keep the conceptual model simple: if URL A, URL B, and URL C are essentially the same page, canonicals are how I tell search engines to treat URL A as the master copy so that the combined signals accrue there instead of being fragmented.

Duplicate content

Search engines use “duplicate content” broadly. In most cases, I’m not dealing with plagiarism - I’m dealing with meaningfully similar content accessible at multiple URLs. If you want a deeper explainer on the mechanics and risks, Moz has a strong overview of duplicate content issues.

Common causes include:

- URL parameters (sorting, filtering, sessions, tracking)

- Trailing slash vs. no trailing slash variants

- Uppercase vs. lowercase URL versions

- HTTP vs. HTTPS (or

wwwvs. non-www) versions - Pagination and index pages that generate multiple accessible routes

- Print-friendly versions or file versions (like PDFs) alongside HTML pages

On B2B sites, I often see this as repeated copy across location pages, a case study published as both HTML and a file, or older service URLs left live after a restructure.

I avoid treating this as a penalty problem. The more consistent risk is signal dilution: crawlers spend time on duplicates, inbound links and internal links get split, and search engines may choose a version that doesn’t match the business intent. Canonicalization is one of the cleanest ways I have to reduce that ambiguity - provided I’m using it for truly similar pages and not forcing unrelated pages into one canonical target.

How to add a canonical tag

Adding canonical tags is less about typing a line of HTML and more about being consistent. Before I touch implementation, I decide what the preferred URL format is (protocol, host version, trailing slash rules, and which parameters - if any - belong on canonical URLs). Once that’s clear, I apply a small set of rules:

- Use a self-referencing canonical on the preferred page. The page I want indexed should declare itself as canonical.

- Point intentional duplicates to the preferred page. If a variant needs to stay accessible (for tracking, print views, or near-identical filtered lists), it should canonical to the clean, preferred URL.

- Use absolute URLs in canonicals. I use the full URL (including protocol and host) to avoid ambiguity.

- Keep exactly one canonical tag per page, placed in the

<head>. Multiple canonicals create mixed signals and are easy to introduce accidentally through stacked templates or plugins.

For content types without an HTML <head> (for example, files), I can’t rely on an on-page tag. In those cases, I use a canonical signal at the HTTP header level so crawlers can still connect the file back to the preferred HTML version.

If you’re auditing at scale, internal links should overwhelmingly point to the canonical version. (Here’s a revenue-first framework for that: B2B SEO Internal Linking: A Revenue-First Model for Service Sites.)

301 redirect vs canonical tag

Both 301 redirects and canonical tags help consolidate duplicates, but I use them for different intent.

A 301 redirect is a move: users and crawlers are sent to a new URL, and the old URL is expected to disappear from results over time. A canonical is a consolidation hint: multiple URLs can remain accessible, but one is treated as the primary version for indexing and signals.

| Aspect | 301 Redirect | Canonical Tag |

|---|---|---|

| User experience | User is sent to the target URL | User remains on the current URL |

| Indexing intent | Old URL should drop out over time | Variants may remain accessible (and sometimes indexed) |

| Best fit | Replacement, removal, migrations | Tracking/filter variants or intentionally similar pages |

I use canonicals for parameterized campaign URLs that I still need for measurement, and I use redirects when an old service page has been replaced by a new URL that should take over permanently.

For international setups, I keep canonical and hreflang roles distinct. Canonicalization is about consolidating similar versions; hreflang is about serving the right regional/language version to the right user. In most cases where each country or language page is genuinely meant to rank in its own market, I give each one a self-referencing canonical and then connect them with hreflang signals - rather than canonicalizing everything back to one master country page.

How to test canonical tags

Implementation is only half the work. After changes, I verify whether search engines are actually accepting my canonical signals.

At a minimum, I check a sample of important pages and compare what I declared as canonical to what the search engine selected as canonical. When they don’t match, I usually find a conflicting signal somewhere - internal links pointing to a different version, a sitemap listing a non-canonical URL, redirects that change the destination, or the canonical target being weak (or not consistently accessible). If you’re debugging why key pages are not showing up the way you expect, Indexation Triage: Finding Why High-Intent Pages Don’t Rank is a helpful companion process.

When I’m troubleshooting, I work through a tight sequence before I change anything else:

- Confirm the canonical target returns a 200 status and is crawlable.

- Confirm the canonical target is not blocked (for example, by

robots.txtor other crawl restrictions). - Ensure sitemaps and internal links mostly reference the canonical version, not variants.

- Reduce unintended differences between pages that are supposed to be duplicates (when practical), so the canonical relationship makes sense.

Timing varies. If a site is crawled frequently, updates can be reflected in days for high-importance URLs; deeper pages can take longer. I plan for that delay, especially after migrations or template changes that affect thousands of pages at once.

Canonicalization mistakes

Most canonical problems I see aren’t advanced - they’re inconsistent. A canonical target blocked from crawling breaks the signal chain. Canonicals pointing at error pages (4XX/5XX) make the whole setup look unreliable. Canonical chains (A → B → C) and loops (A → B → A) add unnecessary complexity and increase the chance that search engines ignore the intent.

Pagination is another repeat offender. When I force every paginated URL to canonicalize to page one, I risk pushing deeper content out of the index. In most paginated series, self-referencing canonicals are the safer default unless there’s a very specific reason to consolidate.

International setups also go wrong when canonicals and hreflang contradict each other - such as a UK page canonicalizing to a US page while hreflang claims the UK page is its own regional result. If I’m building regional pages to rank independently, I keep them canonical to themselves and let hreflang handle audience targeting.

Finally, I avoid using canonicals to hide thin pages instead of fixing them. If a page shouldn’t exist, I retire it properly (redirect or remove). If it should exist, I improve it. Canonicals are best when they reflect reality: multiple URLs, substantially the same page, one preferred version.

.svg)