Most B2B service companies hit a strange point in growth: the dashboards look clean, but the business feels messy. Revenue forecasts swing, marketing insists the leads are fine, sales says the CRM is polluted, and support leaders complain that ticket tags are meaningless.

In my experience, it’s rarely one catastrophic failure. It’s a steady stream of small data errors - especially inside free text - that slip past old rule-based checks and manual QA. That’s where modern data quality validation, plus careful prompt engineering with large language models (LLMs), becomes practical: not to “do AI,” but to help systems judge whether records make sense in context.

Why “clean dashboards” can still hide broken decisions

Traditional validation was built for tidy tables: email regex, “not null” checks, “value in allowed list.” That still matters, but B2B teams now run on a mix of structured fields and language-heavy inputs that don’t behave like clean columns.

A typical B2B service org doing $50K-$150K/month (or more) often relies on a stack that includes:

- CRM and marketing automation fields

- Sales notes and call transcripts

- Support tickets and chat logs

- Product usage events and analytics logs

- Contracts, proposals, and other long-form documents

Classic checks mostly “see” the first category and ignore the rest. The result is leadership debates built on partial truth: pipeline stages that don’t match notes, ticket categories that don’t reflect impact, and “intent” fields filled with guesses.

The cost shows up in weekly KPIs. Pipeline accuracy drops when leads are mislabeled (job seekers tagged as SQLs). Routing breaks when country, industry, or account tier is wrong. Client satisfaction suffers when “bug” tickets get filed as “how-to,” delaying real fixes. Compliance teams end up manually hunting for missing clauses or risky exceptions that never got tagged.

A common pattern I see: a small portion of records pass even basic quality checks, but reporting still treats all rows as equally trustworthy. That’s how you end up with clean but wrong dashboards - and strategy arguments that are really data trust arguments.

This isn’t a niche problem. Harvard Business Review has highlighted how little corporate data meets basic quality standards, which matches what many teams experience once they look beyond surface-level field checks.

Where traditional validation breaks for modern B2B data

The deeper issue isn’t just that rules fail sometimes - it’s that fixed rules can’t keep up with how people describe reality.

People now interact with systems in natural language: emails, chat, call summaries, form fields with “other,” internal notes, and open-text reasons for churn. Meanwhile the business changes quickly: new offerings, new tiers, new ICP definitions, new markets, new partner motions. Your taxonomy (and the validation rules tied to it) often stays frozen.

Rule-based systems still excel at “hard constraints” (a quantity must be positive; a required field must exist). But they struggle with cross-field consistency and meaning. For example: a lead note can clearly indicate “budget approved, wants pricing in two weeks,” while the CRM stage says “cold.” No regex can reconcile that. Similarly, a ticket can include language indicating “production down,” while the tag says “question.”

This is where context-aware validation matters: checks that ask, “Does this record make sense given the evidence we have?”

What LLM-based validation adds (and what prompt engineering means)

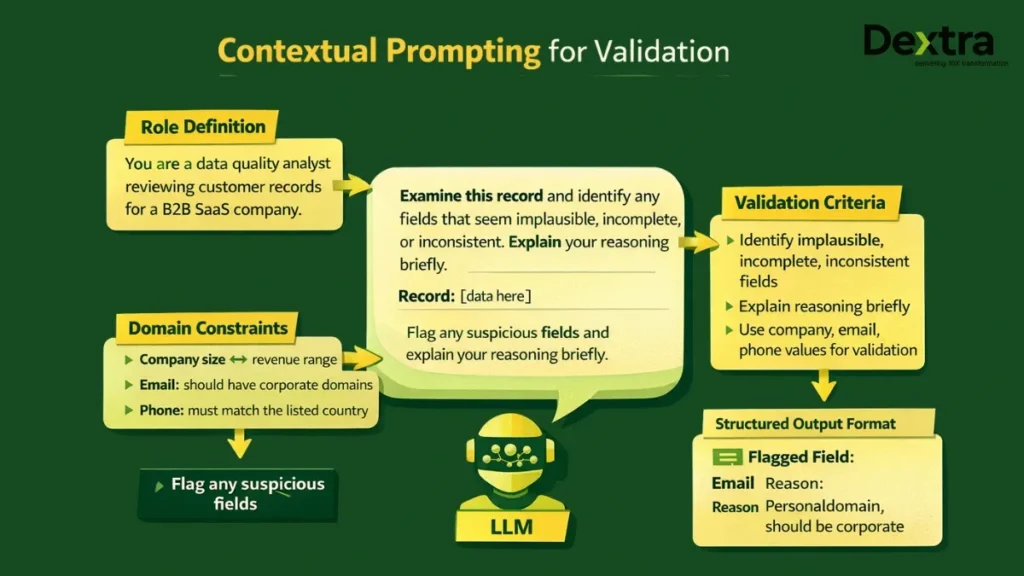

In this context, prompt engineering isn’t academic. I treat it as writing explicit instructions, constraints, and examples so an LLM can evaluate or label data consistently.

Instead of telling a model “fix my CRM,” a useful prompt frames a narrow task and forces a structured output, such as: return JSON with valid_stage (true/false), suggested_stage, confidence, and evidence (quotes from the note). That structure matters because it makes the model’s output usable in systems and review queues.

Compared to rule-based validation, LLMs tend to help most when meaning is embedded in free text, when the “truth” requires reasoning across multiple fields, and when the issue is ambiguity (intent, urgency, impact) rather than format.

I don’t see this as replacing rules. A mature approach is hybrid: deterministic checks handle schema and hard constraints; LLMs handle interpretation, consistency, and language-heavy fields.

From hard rules to contextual reasoning in real workflows

Here are a few patterns where contextual validation changes outcomes.

Lead qualification notes: A rep writes, “Spoke with VP Ops. Series B, 35 FTEs. Need to cut manual reporting time before next board cycle. Asked for pricing in 2 weeks.” A rule-based system might only confirm the notes field isn’t empty. A well-designed prompt can extract signals (role, urgency, company size), compare them to ICP criteria, and flag inconsistencies like “stage says early research but note indicates active evaluation.”

Support tickets and conversations: A ticket says, “Your latest update broke our reporting API. Our dashboard is blank before month-end close.” The text contains impact, urgency, and scope. An LLM can classify this as a bug with high business impact, attach a product area label, and suggest escalation - even when the original tag is wrong.

Contracts and order forms: For document-heavy processes, LLMs can assist by checking whether required sections are present, whether terms match a standard range, and whether unusual clauses appear. This isn’t about letting a model “approve” legal language; it’s about flagging what deserves human review and making omissions harder to miss. If RFPs and long packages are part of your funnel, pairing validation with context-aware document search for long RFP packages can reduce missed requirements and duplicated review cycles.

The key difference is that validation becomes “reasoning with evidence,” not just checking whether a field is empty.

Quick wins, human review, and how production systems stay sane

Leaders usually want two answers: where impact shows up quickly, and where humans still must stay in control.

What tends to move fast is anything that improves labeling and routing without changing contractual outcomes: intent classification for inbound inquiries, re-labeling ticket categories for better triage, flagging suspicious records in high-value accounts, and detecting mismatches between free text and structured stages. What should stay human-led includes final decisions with legal, financial, or compliance implications, plus the design of taxonomy definitions (because those definitions are business policy, not “data science”).

- Fast-impact areas (often weeks, not quarters): intent and segment classification on inbound text; duplicate detection when fields are close-but-not-identical; ticket re-tagging using full text; inconsistency flags for key records (pipeline, renewals, escalations).

- Human-controlled areas: approvals tied to legal/finance/compliance; final taxonomy naming and definitions; threshold tuning to avoid alert fatigue and bias; periodic reviews of edge cases and drift.

This also answers a common operational question: “How is this used in production?” I typically see three patterns: batch jobs in the warehouse (nightly or hourly), real-time checks at data entry (forms, ticket creation), and scheduled re-validation on critical datasets (open pipeline, renewals) so old records don’t silently rot.

A practical reference architecture (without locking into specific vendors)

I think about LLM validation as a pipeline with explicit guardrails.

Data comes from operational systems (CRM, ticketing, analytics, email/chat exports, document stores) into an ingestion layer. A preprocessing step normalizes identifiers, dates, and metadata, and chunks long texts like transcripts so the model sees coherent segments. If you’re formalizing this at the data layer, it helps to build the foundation first with marketing data lakes that serve LLM use cases.

A prompt layer then applies task-specific templates (validation, enrichment, intent labeling). For reliability, prompts should define allowed labels, required output fields, and examples - including negative examples that show what “wrong” looks like.

The inference layer calls a chosen model (hosted or self-managed) and returns structured outputs. Then a scoring step applies thresholds: high-confidence outputs can update downstream fields or routing; medium-confidence outputs go to a review queue; low-confidence cases fall back to deterministic rules or “no change.”

Finally, monitoring closes the loop: prompts and model versions are logged; disagreement rates are tracked; drift is watched across time, segments, and regions. If you care about audits, this logging is not optional - it’s the system of record for “why did we label it that way?”

This approach also addresses explainability. If I need the system to be auditable, I require outputs to include evidence anchored in the input text (short quotes or references), not vague rationales. That makes later reviews and stakeholder trust much easier.

Building user-intent taxonomies from real logs (and validating them)

User intent taxonomies can sound like academic research, but in B2B services they directly shape routing, reporting, and prioritization. They influence how you bucket site searches, chat requests, contact forms, email inquiries, and “reason for contact” fields.

A practical method starts with real data (search logs, chat transcripts, inbound emails, sales/support notes), removes unnecessary sensitive details, and samples across weeks and channels so you don’t build a taxonomy from one unusual day.

Then I use LLMs (for example, GPT-4) to propose an initial set of high-level buckets (often 4-8) with short definitions and examples. For B2B services, common buckets include information seeking, vendor comparison/pricing, implementation/onboarding, support/troubleshooting, expansion, and cancellation risk. That draft is only a starting point.

Validation matters. Sales, CS, and product stakeholders should review the bucket names and boundaries using the language they actually use internally. After that, I test the taxonomy on held-out logs the model hasn’t seen, compare model labels to human labels on a subset, and quantify agreement. If you need a formal measure, inter-annotator agreement metrics (like Cohen’s kappa) can help reveal whether the taxonomy itself is too ambiguous.

This is also where I set expectations: yes, LLMs can generate and apply taxonomies at scale, but they shouldn’t be the final authority on what your business “means.” Humans own definitions; models operationalize them.

What makes a taxonomy “good,” and how I keep it from drifting

A useful taxonomy is not the one with the most categories. It’s the one that reduces ambiguity and supports decisions.

I look for coverage (almost every log fits somewhere with minimal “Other”), low overlap (analysts don’t constantly hesitate between labels), business relevance (each category maps to an action like routing or content prioritization), and reporting usability (you can trend it over time by channel, region, and segment).

Then comes governance - the unglamorous part that prevents chaos. Without ownership, marketing invents one taxonomy, CS invents another, and product builds a third, which makes cross-team reporting meaningless. LLMs can accelerate label creation, so drift can spread faster unless there’s a shared source of truth for definitions and prompt versions.

When new offerings launch, I explicitly decide whether the change requires a new top-level intent, a sub-intent, or just updated examples inside an existing label. Monitoring should flag “unknown/other” rates rising and disagreement rates increasing - those are common early warnings that your taxonomy no longer matches reality.

Real-world applications across CRM, support, and analytics

Once validation and intent labeling are reliable enough, the use cases become concrete.

On the CRM side, contextual checks can flag job titles that don’t match seniority fields, company names that look fake, and pipeline stages that contradict notes. That improves segmentation and reduces wasted outbound effort. For deduplication, LLMs can help compare “near duplicates” where names, domains, and notes are slightly different, then propose whether two records likely represent the same account or contact.

For inbound inquiries, intent labeling helps separate “just researching” from “evaluating” from “ready to talk,” which supports better routing and response-time focus. If you want to connect this to revenue impact, intent labels pair naturally with AI for B2B customer journey mapping and AI-based win-loss analysis to surface where misclassification is slowing deals down.

Support teams often see fast gains from reclassifying ticket tags using full-text content, identifying themes for engineering, and spotting repeated incidents that may signal churn risk. The consistent thread is the same: labels become more faithful to evidence, and downstream decisions become less noisy.

The business case: costs, upside, and realistic timelines

Costs usually fall into three buckets: model usage (often priced per token/call), engineering time for pipelines and monitoring, and human time for review and initial labeling.

I’m cautious with ROI claims because the outcome depends heavily on volume, process maturity, and how quickly teams act on the labels. Still, it helps to frame upside in operational terms: hours saved on manual cleanup, fewer misrouted high-intent leads, fewer escalations caused by misclassified tickets, and fewer leadership decisions made from misleading dashboards. Even broad industry estimates are sobering - $12.9 million annually is a commonly cited figure for the average cost of poor data quality.

A simple back-of-the-envelope model can keep expectations grounded. If you generate 5,000 leads per month and only 10% are truly high-intent, small improvements in correctly labeling and routing that 500-lead subset can matter more than “improving overall lead quality” by a vague percentage. The key is to connect the validation work to a measurable bottleneck: response-time SLAs on high-intent inquiries, forecast accuracy on late-stage pipeline, or escalation rates in support.

Implementation timing is usually fastest when I keep the scope narrow. A typical pattern is: early weeks for data review and success metrics, then prompt and pipeline setup with shadow-mode testing, then limited production rollout for one workflow. If the labels aren’t used to change routing, prioritization, or reporting logic, the “AI project” will look like it failed even if the model is accurate.

Risks, ethics, privacy, and auditability (what I don’t ignore)

LLM validation introduces real risks: hallucinated details, inconsistent outputs across versions, false positives that create alert fatigue, and drift as prompts evolve. On top of that are privacy and governance concerns, especially when sensitive data could be sent to third-party APIs or processed outside required regions.

There are also fairness concerns. If a model systematically labels certain industries, countries, or job titles as “low quality,” you can end up with unequal response times and biased pipeline treatment - often without anyone noticing until outcomes shift.

Mitigation is practical, not magical:

- Keep humans in the loop for high-impact decisions and use conservative thresholds to avoid automatic action on uncertain cases.

- Log inputs, prompts, outputs, model versions, and final actions so decisions are explainable and auditable later.

- Require structured outputs with evidence anchored in the text (quotes or references), not just “because I think so.”

- Mask or tokenize sensitive data when possible, and choose deployment options that meet residency and policy requirements.

- Run periodic bias and performance checks across segments (region, industry, company size) and investigate systematic disagreement with human labels.

For regulated industries, the same principles apply but with stricter controls: tighter data handling, stronger audit logs, narrower scopes at first, and explicit approval workflows for any automation that touches eligibility, pricing, or access. If you’re testing workflows like this, using secure AI sandboxes and data access patterns can help you iterate without accidentally widening exposure.

Where LLM validation and intent modeling are headed next

I expect a few trends to shape what “good” looks like over the next couple of years.

First, multi-step validation will become more common: separate checks for schema consistency, intent, risk, and policy match, combined into a single decision with traceable evidence. Second, retrieval-based validation will reduce hardcoding: prompts can reference current policy docs, schemas, and definitions pulled from internal sources, which helps keep outputs aligned with the latest rules. Third, teams will get better at generating test cases and edge-case suites so validation logic is evaluated like software, not like a one-off experiment.

On the intent side, I don’t think search logs and chat logs should be treated as the same signal. Search often reflects quick navigation and fact-finding, while chat tends to capture longer, multi-turn problem solving. If I force both into one blunt taxonomy, I usually lose nuance. If I respect the difference, the taxonomy becomes more predictive of what buyers and customers actually need.

The practical path is still simple: pick one measurable workflow, define what “better” means, use prompts to turn free text into consistent labels with evidence, and keep the system auditable. When the labels become trustworthy, the dashboards stop being clean but wrong, and teams spend less time arguing about data and more time acting on it.

.svg)