You can spend six figures a year on marketing, watch dashboards fill up with “conversions,” and still feel like the pipeline is thin. I’ve seen this happen when platform ROAS looks strong, attribution reports look sophisticated, and yet closed-won deals don’t move in proportion.

That gap is where incrementality testing helps. It’s how I separate activity that creates net new demand from activity that mostly captures demand that would have happened anyway.

Why incrementality testing matters for B2B service companies

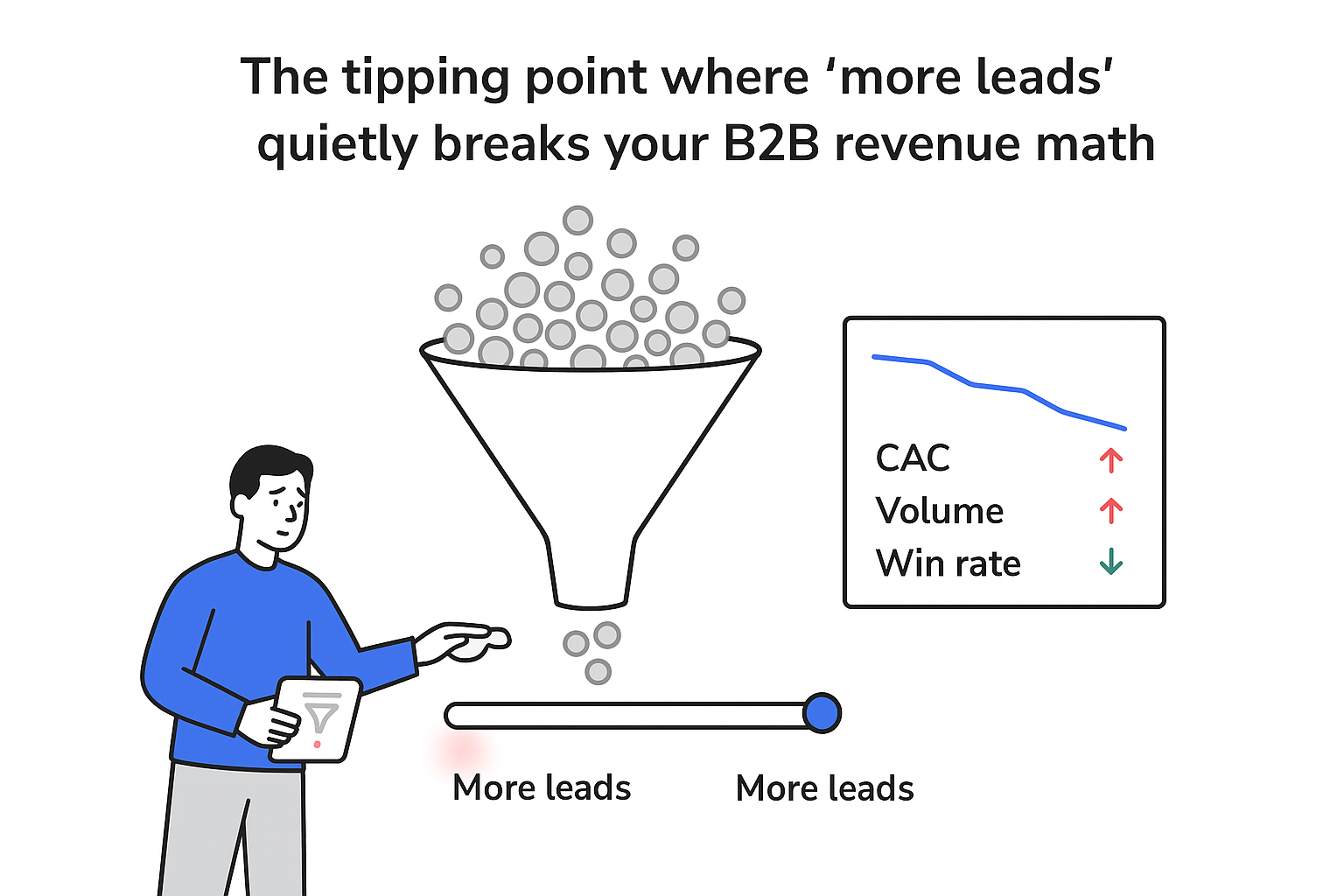

In a B2B service business, the question I care about isn’t “How many leads did this channel drive?” It’s “How much additional qualified pipeline did this channel create that I wouldn’t have seen without it?”

Most reporting doesn’t answer that. Platform dashboards and many multi-touch attribution models mainly redistribute credit across touchpoints for outcomes that already happened. They rarely tell you how many of those outcomes were genuinely incremental.

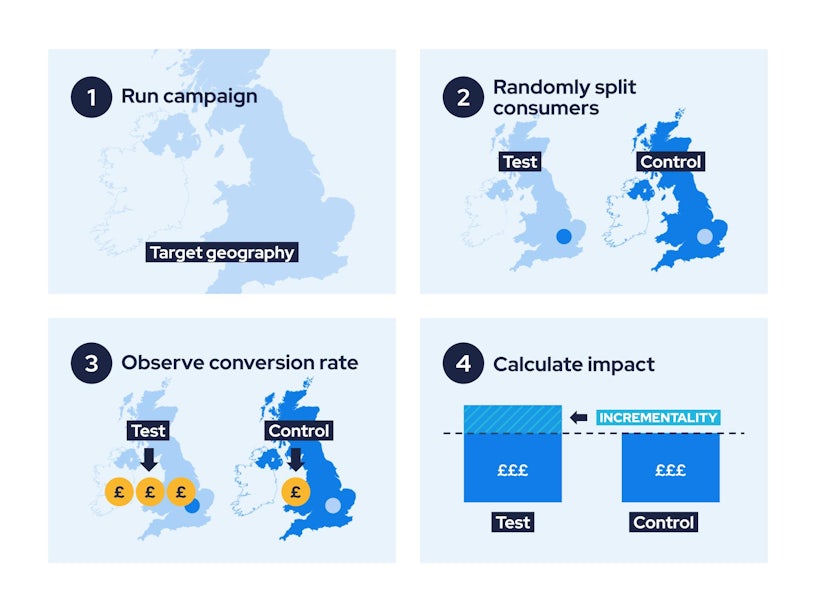

Incrementality testing forces a cleaner comparison between two realities: a group exposed to a channel or campaign versus a similar group that isn’t. The difference is the incremental lift. That lift tends to hold up in budget reviews because it’s framed as a causal question, not a credit-assignment exercise.

The outcomes I actually measure in B2B (not clicks)

For B2B services, I treat incrementality as a way to quantify impact on commercial outcomes, not surface-level engagement. The KPI depends on the sales cycle and data quality, but these are the most common endpoints I use:

- Sales-qualified leads (SQLs) and sales-accepted meetings

- Sales-qualified opportunities and pipeline value

- Closed-won revenue (often with a longer observation window)

That framing also makes your upstream systems easier to stress-test. For example, if a channel “lifts” SQLs but not opportunities, you may have a scoring issue. (If that’s a recurring problem, tightening your sales and marketing SLA and upgrading your lead scoring approach often has more impact than changing bids.)

A realistic example (and what it usually reveals)

Here’s a pattern I’ve seen in B2B consultancies and agencies: a meaningful chunk of paid budget goes to branded search because it reports an excellent ROAS. Sales pushes back with some version of “these accounts already knew us.”

An incrementality test might reduce branded search bids in a subset of territories while keeping everything else stable. Over several weeks, it’s common to see overall revenue barely move while organic/direct absorbs some of the “lost” paid conversions. Sometimes new-logo opportunities dip a bit, but not in proportion to the spend reduction.

In parallel, testing high-intent non-brand search or tightly defined buying-group campaigns often shows clearer incremental lift. The practical outcome isn’t “branded search is bad.” It’s that the business learns where branded search is protective versus where it’s mostly cannibalising existing demand, and budgets can be rebalanced with more confidence. (If you’re building these tests around intent and ICP fit, a clean keyword-to-ICP alignment makes results much easier to interpret.)

What incrementality testing is (in plain language)

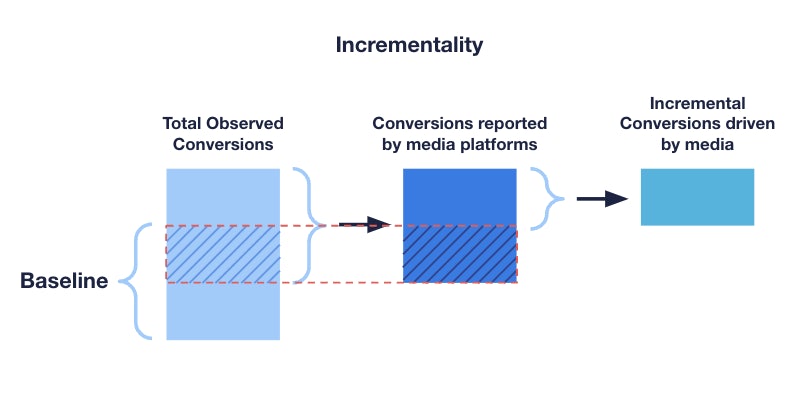

Incrementality is the extra impact marketing creates compared with a similar scenario where that marketing doesn’t run.

So incrementality testing is a set of experiments (or quasi-experiments) that answer: “If I turn this specific activity on for Group A, and keep it off (or reduce it) for Group B, what changes?”

That “activity” can be a whole channel, a campaign, a budget level, a bidding approach, creative/messaging, or even a service-bundle positioning - anything where you can isolate a change and keep the rest as close to business as usual as possible.

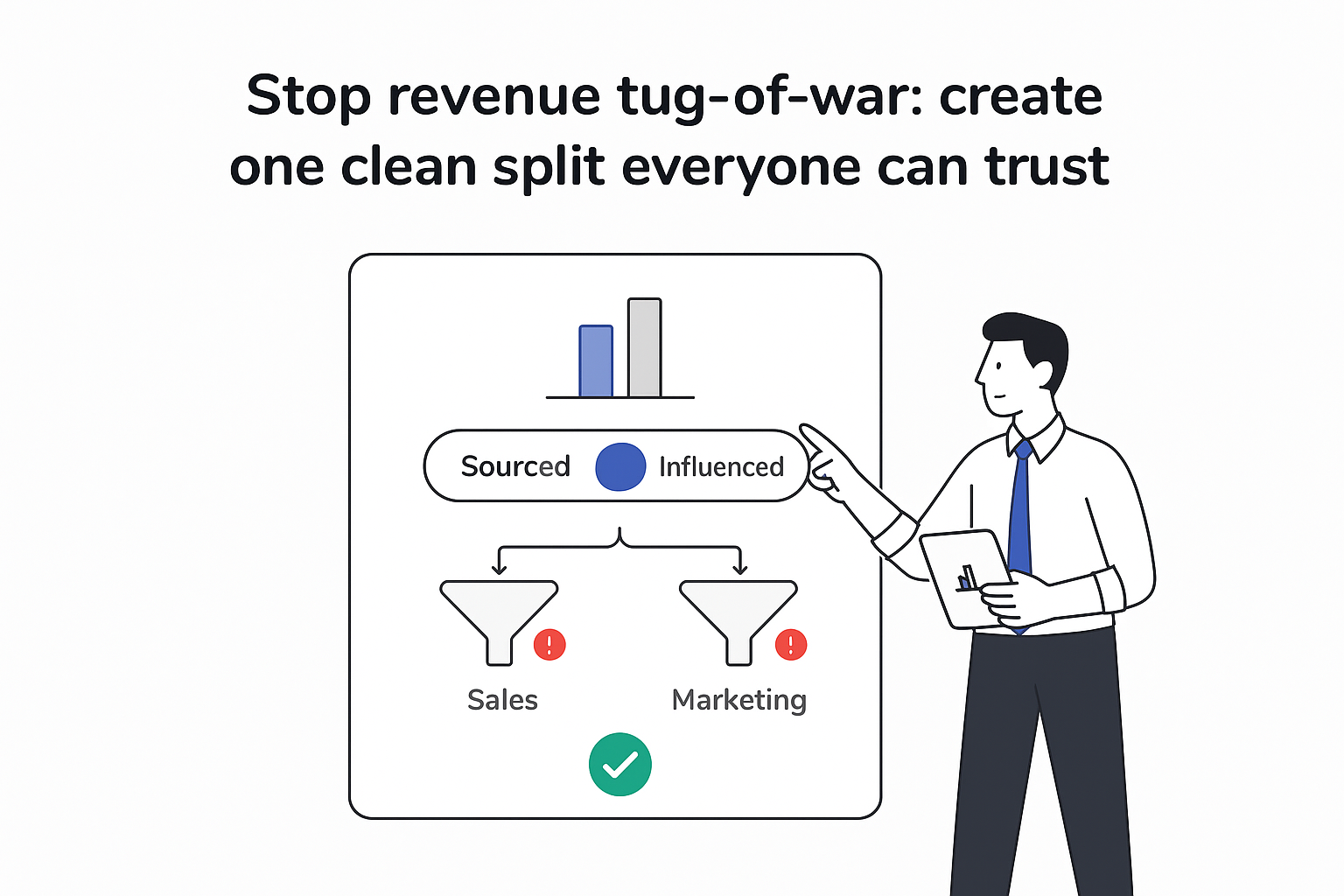

Incrementality vs attribution (why both can be true)

Attribution and incrementality answer different questions, and confusion here is a major reason teams talk past each other.

Attribution asks: Given the conversions that happened, how should credit be split across touchpoints?

Incrementality asks: Which conversions would not have happened if I removed (or reduced) this activity?

Attribution is useful for operational optimisation - what to tweak this week, what messaging appears in journeys, where handoffs happen. But attribution alone can’t reliably answer the “would it have happened anyway?” question, especially in B2B where sales cycles are long, multiple stakeholders influence outcomes, and offline touches matter. Ad platforms also naturally tend to report in ways that maximise visible value for their own inventory, which is another reason I prefer having an incrementality layer.

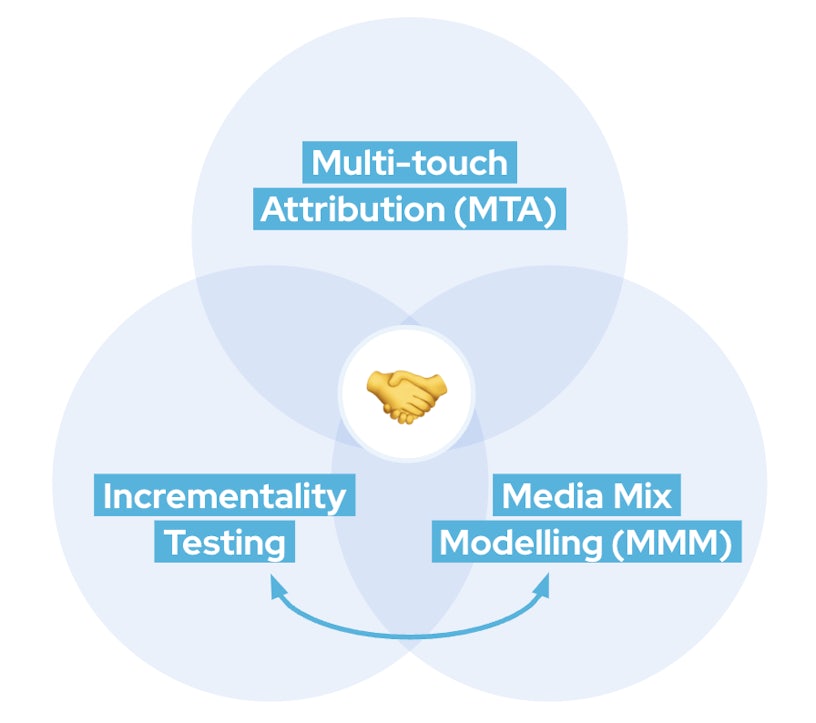

How I think about triangulation (one table, three lenses)

I don’t treat incrementality testing as a replacement for everything else. I treat it as a hard reality check that complements faster-but-less-causal views.

| Method | Main question | Strengths | Limits in B2B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attribution (last click / multi-touch) | Who gets credit for conversions that occurred? | Great for journey insights and quicker optimisation cycles | Doesn’t answer “would it have happened anyway?”; weak on offline and long cycles |

| Incrementality testing | What extra outcomes did this activity create? | Closest practical path to causal lift; connects well to pipeline and revenue | Needs careful design and enough volume/time |

| Marketing mix modelling (MMM) | How do channels/spend relate to outcomes over time? | Useful for budget allocation across longer windows | Data- and skill-intensive; less granular for day-to-day decisions |

When incrementality testing is worth the effort

I don’t run incrementality tests for every small campaign tweak. I prioritise them when the financial stakes are high or when reporting is likely misleading.

I usually trigger a test when one or more of these are true:

- A channel is taking a large share of spend or “claimed” revenue

- ROAS looks implausibly good (especially for branded search or retargeting)

- I’m entering a new region/vertical and need proof of impact

- I’m trying to set a rational split between demand capture and demand creation

In B2B, I also separate short-horizon questions (SQLs, opportunities) from longer-horizon ones (brand effects, future pipeline). It’s possible to test upper-funnel activity, but you need longer measurement windows and disciplined leading indicators. If your “leading indicators” are noisy, tightening your intent signal scoring can make upper-funnel tests far more decision-useful.

How I design an incrementality test without overcomplicating it

The best tests are simple, specific, and hard to misinterpret. Design choices usually matter more than fancy math.

- Define one sharp question (for example, incremental SQLs from paid social to cold accounts in a defined segment over 12 weeks).

- Pick a primary KPI that maps to revenue (SQLs, opportunities, pipeline value, closed-won).

- Choose the test unit (geo, account list, user/cookie, or service line).

- Create test and control groups via randomisation where possible, or matching where randomisation isn’t feasible.

- Set duration and minimum volume so results aren’t dominated by noise (often 6-12 weeks for pipeline metrics; longer for revenue).

- Lock “business as usual” outside the variable being tested (sales motion, follow-up, pricing, email sequences).

If I can’t keep the rest of the system stable, I don’t trust the result - even if the numbers look clean. For teams that are still building a testing habit, it can help to standardise the basics first (see simple A/B testing for busy teams), then graduate to incrementality once execution is reliable.

Common pitfalls I plan for (because B2B is messy)

Most failed incrementality tests fail for operational reasons, not statistical ones. These are the issues I watch first:

- Contamination/spillover: accounts or users unintentionally get exposed (common in geo tests and account-based programs).

- Seasonality and timing: quarter-end pushes, holidays, events, or pricing changes distort comparisons.

- Sales-behaviour drift: a new SDR manager, routing change, or comp-plan shift during the test can swamp marketing effects.

- Algorithmic shifts: platform delivery changes can look like “lift” unless test and control run simultaneously.

If any of those happen, I document them and interpret results as directional rather than definitive. This is also where post-click experience can quietly ruin a good test - if your landing page message is drifting between groups, you’re no longer testing one variable (see landing page message match).

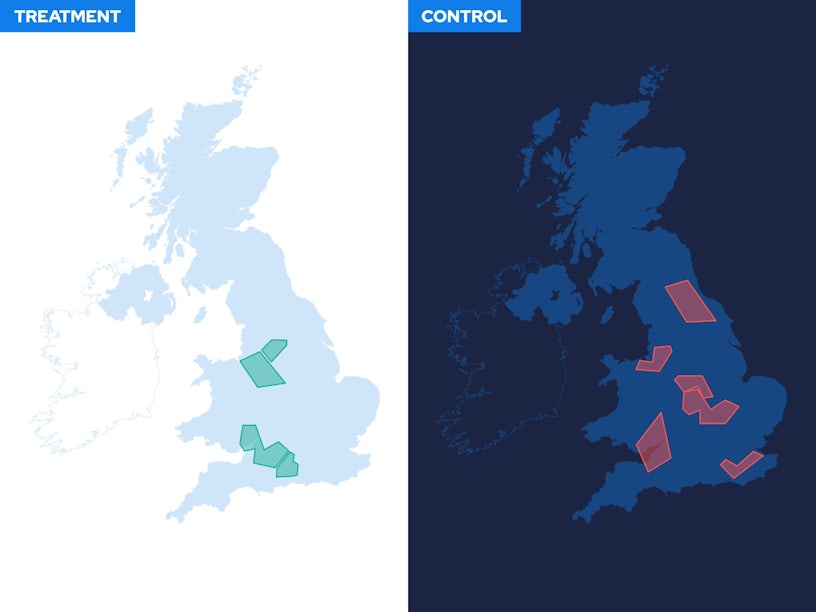

Picking the right test type: geo, holdout, or synthetic control

When I can, I prefer holdout tests at the account or user level because they’re conceptually clean: some get exposed, some don’t, and I compare downstream outcomes.

Geo experiments are often more practical for broad-reach channels (search, YouTube, wider paid social) and for situations where user-level tracking is unreliable. The tradeoff is spillover risk - people move, travel, and browse across regions - so I use larger geos or clusters and try to pick areas with less overlap.

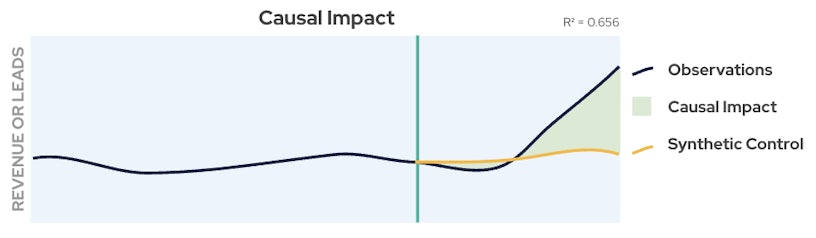

When neither geo nor holdouts are feasible (for example, a change rolled out everywhere at once), I use a synthetic control approach: building a credible “what would have happened” baseline from historical performance, trend adjustments, and comparable unexposed segments.

To keep synthetic controls honest, you need explicit model validation. That often includes tracking forecast error and fit metrics like root-mean-square-error (RMSE). Under the hood, teams commonly use techniques such as linear regression or time-series approaches like ARIMA to forecast counterfactual performance.

How I calculate incremental lift (a simple walkthrough)

At its core, I’m always doing three things: counting outcomes in test and control, estimating the baseline for the test group without the change, and measuring the gap.

Example: 2,000 accounts split evenly.

Test: paid social + existing email/SDR motion

Control: existing email/SDR motion only

After 10 weeks:

Test: 40 SQLs, 12 opportunities, 4 closed deals

Control: 30 SQLs, 8 opportunities, 3 closed deals

Incremental outcomes are the differences: +10 SQLs, +4 opportunities, and +1 deal. If average deal size is $40k and the incremental deal is real, that’s $40k incremental revenue.

From there, I translate lift into unit economics (incremental cost per SQL, per opportunity, and incremental ROAS) because those are easier to defend than platform conversion counts. In practice, I often normalise by rates (for example, SQLs per 1,000 accounts) when group sizes differ, and I sanity-check pre-test similarity so I’m not mistaking a pre-existing gap for a marketing effect.

How I interpret results and decide what to do next

Once I have lift numbers, I focus on three decision filters: whether the effect looks real (not noise), whether it’s meaningful financially, and whether it’s consistent down-funnel.

If lift shows up in leads but not in opportunities or revenue, I assume I’m buying volume without improving quality - or I’m measuring too early in the cycle. If lift contradicts attribution (which happens a lot), I don’t panic. I keep attribution for short-cycle optimisation and use incrementality to make the larger budget and channel-mix decisions.

Over time, I’m aiming for a simple rhythm: a few well-designed tests a year on the highest-stakes questions, with results that can be explained in one slide - reported conversions versus incremental outcomes - so finance and leadership can make calmer decisions based on net new pipeline, not just reported ROAS.

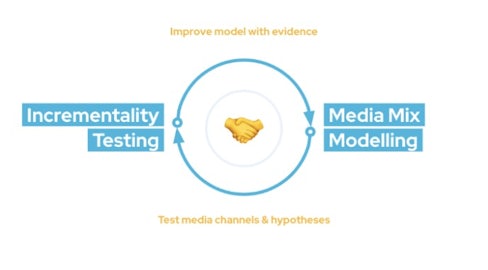

Building a sustainable measurement approach (so this isn’t a one-off)

After a few tests, incrementality becomes less of a “science project” and more of a management habit. The structure that tends to work in B2B services is straightforward: use attribution for day-to-day decisions, run recurring incrementality tests on the channels most likely to be overstated (often branded search and retargeting) or most strategically important (often upper-funnel paid social), and add MMM only when spend and channel complexity justify it.

The goal isn’t perfect measurement. It’s decision-grade clarity: knowing which spend actually creates incremental SQLs, opportunities, and revenue - so you can protect what truly works, cut what only looks good in dashboards, and explain the tradeoffs in plain business terms.

.svg)