If I run a SaaS company long enough, I eventually hit the same moment: runway changes month to month, the “final_final_v18.xlsx” file multiplies, and a simple question like “What happens to ARR if I add two reps next quarter?” takes days to answer with confidence.

That combination - uncertainty, disconnected data, and slow modeling - is what SaaS budgeting and forecasting software is designed to reduce.

SaaS budgeting and forecasting software for predictable growth

SaaS budgeting and forecasting software brings financial actuals, subscription metrics, and operating plans into a single model. Instead of stitching together spreadsheets and exports, I can see how headcount, pipeline, churn, and spend connect to revenue and cash over time - and I can update assumptions without breaking the logic.

At a practical level, a solid planning setup typically helps me:

- Centralize data from billing, CRM, HR, and accounting

- Build driver-based models (headcount, quotas, churn, usage) that reflect how the business actually grows

- Run scenarios so decisions map to ARR, burn, and runway

- Keep budget vs. actuals current so I can course-correct earlier

The point is not to eliminate uncertainty - SaaS will always have it. The point is to cut avoidable noise (manual updates, mismatched numbers, hidden formula errors) so the leadership team can make faster, clearer decisions when performance or market conditions change. If you are actively moving away from spreadsheets, it helps to see what automating your SaaS budgeting and financial planning looks like in practice.

What SaaS budgeting means in a subscription business

Traditional budgeting assumes a more linear motion: sell a product, recognize revenue, incur costs, repeat. Subscription businesses behave differently. Revenue shows up as MRR/ARR over time, and it changes through renewals, churn, expansions, downgrades, and pricing shifts. That means SaaS budgeting is less about picking a single annual growth rate and more about planning the drivers that create (or destroy) recurring revenue and cash.

I find it helpful to keep three concepts separate even though they are related. A budget is the yearly plan and targets. A forecast is the updated view of where the year will actually land based on recent performance. And scenarios are “what-if” versions that pressure-test decisions like slower hiring, higher churn, or a delayed product launch.

Under the hood, most SaaS budgets rely on a small set of operating metrics. Definitions vary by company, but the foundation usually includes MRR/ARR, churn rate (customer or revenue), net dollar retention (NDR), CAC, payback period, LTV, gross margin, burn rate, and runway. If your team needs a quick baseline definition for the recurring model itself, Sage’s glossary on Recurring revenue is a useful reference.

Once those drivers are explicit, the planning work becomes easier to explain: assumptions flow into a model, and the model produces outputs like an ARR bridge, cash forecast, and scenario comparisons.

Where SaaS budgets usually break (and what to watch)

Most budgeting pain in SaaS does not come from “doing finance wrong.” It comes from trying to run a dynamic subscription model on tools and workflows that do not update cleanly.

Assumptions change faster than spreadsheets. Win rates, quota capacity, conversion rates, and churn rarely stay stable for 12 months. When every change forces manual edits across multiple tabs and versions, the model becomes fragile - and people stop trusting it.

Revenue streams are rarely simple. Many companies mix self-serve subscriptions, sales-led contracts, usage-based charges, add-ons, and services. If I model everything as one blended growth number, I lose the ability to explain why ARR moved or which lever actually matters.

Churn and expansion are not “one cell” problems. Treating churn as a flat percentage can hide segment risk and cohort behavior. A price-sensitive cohort, a specific plan tier, or a single enterprise account can dominate the outcome. Planning gets more realistic when churn and expansion are modeled at least by segment, plan, or cohort. (If you want a practical segmentation starting point, this framework on Customer segmentation for founders: four groups that matter maps well to churn and NDR planning.)

Data fragmentation slows everything down. If billing, CRM, and accounting disagree - or if the team is constantly exporting CSVs - budget vs. actuals becomes a monthly fire drill. The longer it takes to reconcile numbers, the later I spot risk.

Ownership is unclear outside finance. When only finance can touch the model, department leaders often treat the budget as something that happens to them instead of something they own. That is when hiring plans drift, spend surprises appear, and forecasting turns into explanations after the fact.

Core components of a SaaS budget

Even though each company has its own quirks, most SaaS budgets share the same building blocks. I typically see the plan organized around:

- Revenue (starting MRR, new, expansion, contraction, churn)

- COGS (hosting/infrastructure, support/onboarding, delivery and processing fees)

- Operating expenses by function (Sales and Marketing, Product/R&D, Customer Success, G&A)

- Headcount plan (roles, start dates, compensation, taxes and benefits)

- Cash view (timing of collections, burn, runway, and any financing assumptions)

The important part is the linkage. Sales headcount and ramp drive capacity and bookings. Pipeline coverage and win rates influence new ARR. Customer count and usage influence support load and cloud spend. Those pieces then flow through to cash timing. A budget that does not connect these drivers often looks neat on paper but breaks as soon as reality diverges.

Revenue projections and recurring revenue forecasting

Recurring revenue forecasting is most useful when ARR is not treated as a single growth rate, but as a set of moving parts: starting MRR, new MRR, expansion, contraction, and churn. That structure creates an ARR bridge leadership can challenge and improve.

Here is a simple six-month MRR waterfall example:

| Month | Starting MRR | New MRR | Expansion | Contraction | Churned | Ending MRR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 100,000 | 15,000 | 5,000 | 2,000 | 3,000 | 115,000 |

| Feb | 115,000 | 18,000 | 6,000 | 2,500 | 3,500 | 133,000 |

| Mar | 133,000 | 20,000 | 7,000 | 3,000 | 4,000 | 153,000 |

| Apr | 153,000 | 22,000 | 8,000 | 3,000 | 4,500 | 175,500 |

| May | 175,500 | 24,000 | 9,000 | 3,500 | 5,000 | 200,000 |

| Jun | 200,000 | 25,000 | 10,000 | 4,000 | 5,500 | 225,500 |

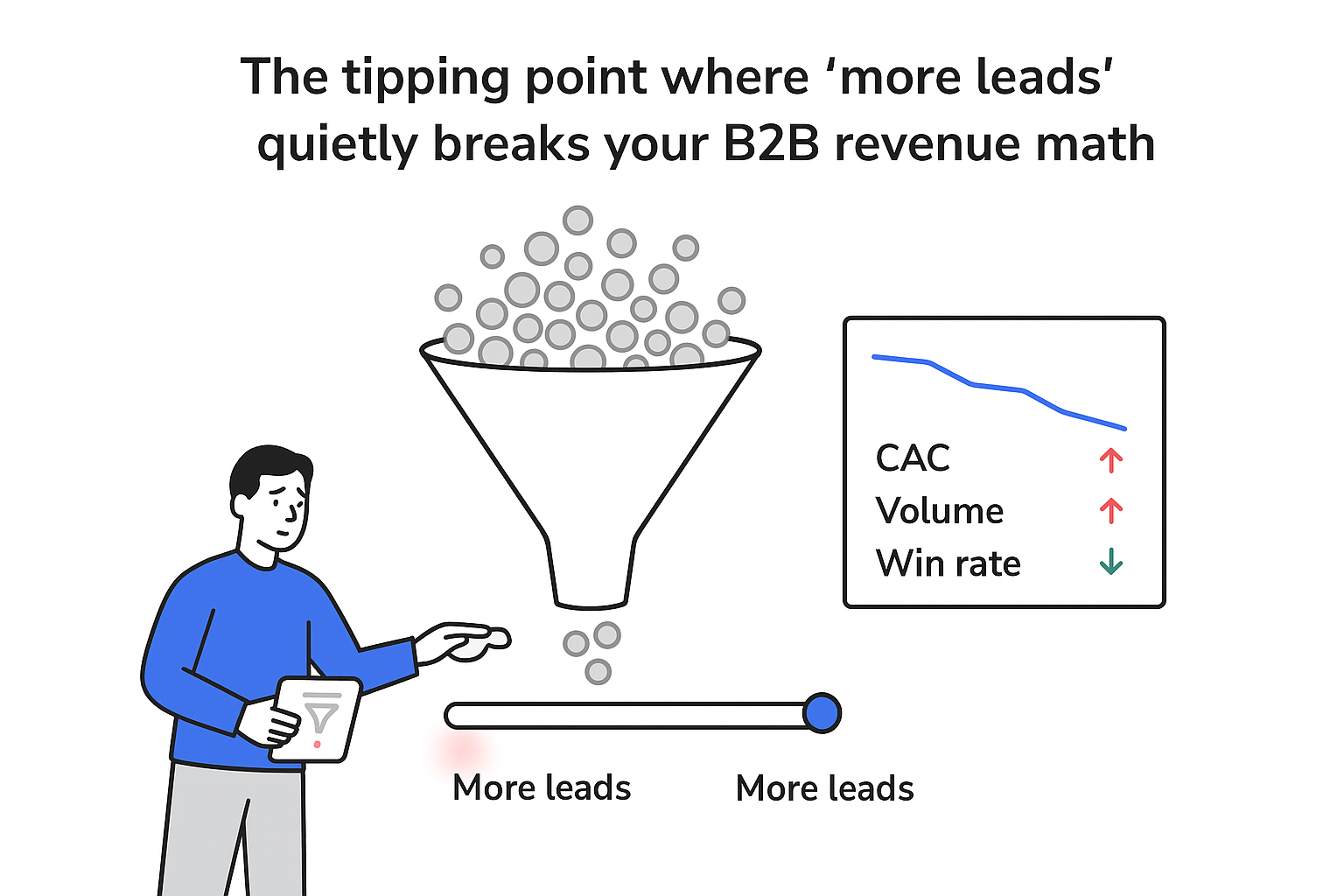

From there, I can scenario-test the levers that actually move the business: a churn increase in a specific segment, a change in expansion behavior after pricing updates, or a dip in win rates that cascades into cash a few quarters later. To keep the revenue side grounded, it also helps to periodically audit your sales pipeline for marketing bottlenecks so your conversion assumptions reflect reality, not last quarter’s spreadsheet.

There are two common modeling mindsets. A top-down view is useful for long-term narrative (market, share, positioning), while a bottom-up view is more reliable for operating plans because it ties to capacity, pipeline, and conversion. The best forecasts usually reconcile both: bottom-up mechanics with a top-down “does this story make sense?” check.

Expense planning and SaaS expense management

On the cost side, most SaaS expense planning comes down to people and the costs that scale with customers and usage. I generally separate spend into headcount (salary, bonus, taxes, benefits) and non-headcount (software, contractors, programs, travel, office), and then map those to COGS vs. operating expenses.

Headcount planning gets more accurate when it is tied to operational drivers rather than hope. Engineering and product plans can connect to roadmap pace. Sales capacity should reflect ramp time and productivity by segment. Customer success can be tied to customers-per-CSM or ARR-per-CSM. Support can track ticket-volume assumptions. Non-headcount spend also benefits from clear drivers, like cloud cost per active user (or per unit of usage) and marketing spend tied to pipeline goals rather than a flat percentage increase.

The biggest improvement usually comes from visibility: seeing spend and headcount changes in the same model as revenue and cash, so I can evaluate trade-offs quickly (for example, adding CSMs to protect NDR vs. accelerating sales hires to push new ARR).

A repeatable SaaS budgeting and forecasting rhythm

A budgeting process works best when it is a year-round rhythm, not a once-a-year sprint that burns everyone out. In practice, I aim for a lightweight cycle: define targets and constraints (growth, runway floor, efficiency goals), build the driver-based plan, agree on a small set of scenarios, and then reforecast on a consistent cadence using fresh actuals.

Department-lead involvement is what makes this sustainable. Finance can own structure and definitions, but sales, marketing, product, and customer success should recognize their assumptions in the model - and be accountable for updating them when reality changes. This is also where clear handoffs matter; a Sales and marketing SLA that makes follow-up happen makes pipeline inputs more reliable, which makes the forecast more reliable.

A monthly or quarterly reforecast is less about “redoing the budget” and more about updating the few assumptions that moved: pipeline conversion, rep ramp, churn in a segment, cloud costs per unit, or hiring timing. If those drivers are explicit, the forecast update becomes a decision exercise instead of a data exercise.

Common budgeting mistakes I watch for

A few mistakes show up repeatedly, even on strong teams. Overestimating growth while ignoring ramp time is one of the most common, especially for sales capacity. Treating churn as a flat rate is another - segment and cohort differences often matter more than the company average. Modeling ARR but not cash timing also creates surprises: annual prepay, multi-year deals, and payment terms can make ARR look strong while cash tightens. Finally, letting the plan go stale turns budgeting into theater; the earlier I see drift in the drivers, the more options I have to respond without panic.

Choosing SaaS FP&A software without overbuying

Not every company needs the same level of planning infrastructure. A seed-stage team with a simple model may prioritize speed and flexibility, while a multi-entity company will care more about audit trails, consolidation, and controlled collaboration.

When I evaluate options, I focus on a few fundamentals:

- Fit to stage and team size (how much structure I need vs. how fast I can operate)

- Revenue-model support (self-serve, sales-led, usage-based, add-ons, multi-year terms)

- Data connectivity (accounting, billing, CRM, and if relevant, a warehouse)

- Model flexibility (multi-entity, multi-currency, cohort or segment modeling, headcount by role and location)

- Usability beyond finance (department leaders can input assumptions without breaking logic)

- Security and governance (permissions, audit logs, sensitive HR and financial handling)

I also try to separate “features” from “workflows.” The best fit is usually the system that makes recurring monthly and quarterly planning motions simpler - not the one with the longest feature list. For teams looking at dedicated tooling, Sage Intacct Planning is one example of software built for structured budgeting and forecasting, and it pairs naturally with subscription management software that keeps recurring revenue inputs consistent.

Using the budget for growth-stage planning and fundraising

SaaS financial planning changes by stage, but the need for clarity stays the same. Early on, the budget is mostly a runway and learning plan - enough spend to reach product-market fit signals without losing control of cash. In the Series A/B range, the plan shifts toward scaling go-to-market with measurable efficiency (CAC payback, NDR) while keeping an eye on burn. Later-stage planning tends to emphasize efficiency and margin, with boards watching metrics like burn multiple and the “rule of 40” (a common shorthand that combines growth rate and profitability margin).

The budget and forecast also become the fundraising narrative in numbers. I want to show how long cash lasts under realistic assumptions, which milestones the business can reach with that cash, and how sensitive outcomes are to churn, pricing, and hiring pace. When the model connects revenue drivers to cash timing, I can answer investor-style questions - like delaying hiring by a quarter or changing spend levels - without turning the next week into spreadsheet cleanup. If marketing is a meaningful spend line, it helps to anchor assumptions with a clear plan to set quarterly marketing goals that map to P&L.

Predictable SaaS growth is less about perfectly forecasting the future and more about building a planning system that surfaces risk early, makes trade-offs visible, and keeps the team aligned on the few drivers that matter most. Markets change and surprises happen; the advantage is seeing the impact while you still have time to respond deliberately.

.svg)